30 Oct Solving the Problem of Post-operative Airway Obstruction in Nasal/Sinus Surgery

A Strategy and New Device to Ensure Patient Safety, Comfort, and Satisfaction

Robert Kotler, MD, FACS *

Beverly Hills, CA

Keith Wahl, MD, FACS *

La Jolla, CA

Kimberly J. Lee, MD, FACS *

Beverly Hills, CA

Packing or No Packing, the Post-operative Period Is not Popular with Patients

Some surgeons choose not to place any packing. But, patients still complain of impaired breathing due to endonasal edema, blood and mucus accumulation. More commonly, however, nasal and sinus surgery typically features some surgeon-inserted “packing,” placed or injected into the nasal fossae, at the conclusion of the operation. In the recent National Interdisciplinary Rhinoplasty Survey, 39% of surgeons reported using packing 81%-100% of the time, with 81% of the surgeons leaving the packing in place for 0-3 days post-operatively.2

Here are the common reasons/indications for packing:

- To stabilize manipulated/repositioned/reconstructed elements in the proper and anatomically correct positions

- To prevent synechiae formation

- To reduce the chance of bleeding and prevent hematoma formation

- To act as a substrate for medications, e.g., antibiotics and steroids

- To act as a conduit for topical medications to be instilled after surgery, e.g., nasal decongestant drops to reduce bleeding and/or relieve congestion

– Clinical Instructor, Department of Surgery, Division of Head and Neck Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA. Corresponding author, rkotler@robertkotlermd.com.

– Partner, A-K Technology Consultants; Clinical Assistant Professor, Retired, UCSD School of Medicine, Division of Otolaryngology, Department of Surgery, La Jolla, CA.

– Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Surgery, Division of Head and Neck Surgery, David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA, Los Angeles, CA.

The Doctor’s Dilemma: Prospective Patients Fear “The Packing”

Today it is common knowledge among the lay public that nasal and sinus surgery require packing. However, and for good reason, nasal packing has had “bad press” for decades.

Patients report that the standard one-to-five-day period of indwelling packing is the most oppressive feature of the entire experience.4 This is not due to discomfort/pain, which generally is not severe and can be controlled with medication. Rather, it is the packing-induced blocked nasal airway that generates acute anxiety and claustrophobia. “It was as if someone left a clothespin on my nose and walked away,” reported one semi-irate patient. Call it “asphyxia anxiety.”

Yet the surgeon has sound reasons to employ packing-the benefits of nasal packing far outweigh the risks. The literature notes significant complications and adverse effects: toxic shock syndrome, septal perforation or other tissue necrosis, and even a profound vagal response. 6, 7, 8 But the odds of major problems are low, and thus percentages still favor employing packing.

One issue that needs to be recognized is that even though nasal packing has a limited post-operative tenure, studies have shown that complete, bilateral nasal packing can also cause obstructive sleep apnea and hypoxemia.5

Accepting that the positives of packing trump the negatives, today’s nasal surgeons have ample choices to serve packings’ assorted missions. Modern biotechnology is now delivering a variety of excellent packing products. Designed to prevent infection, accelerate healing, and reduce bleeding, surgeons have the choice of the mesh, clothlike absorbables, gel-liquids, or the non-absorbable, non-adherent, and easily removable varieties. In addition, there are new packing substances on the horizon, as bioscience is learning to impregnate the materials with biologicals that stimulate healing.

Improving Coexistence Between Packing and an Airway Device: The Win-Win for Patient Safety and Comfort

Surgeons, tinkerers by nature, tend to fixate on surgical technique. We embrace novel technology, innovative instrumentation in the pursuit of patient safety, and improved surgical results and operating room efficiency and economy. In the pursuit of more rapid healing and the prevention of post-operative complications, we focus on the benefits of nasal packing while overlooking the importance of concomitantly maintaining an airway. Maybe we have developed tunnel vision as we labor in the nasal tunnels. Are we losing opportunities to provide our patients with successful operations because we have neglected to also focus on patient comfort and satisfaction? Perhaps, particularly because few of us have stood in the patient’s shoes; “Every so often, a doctor needs to be a patient. He will then be a better doctor.”

Appreciating the face-off between post-operative safety and healing objectives, and comfort, we have examined the products and devices, past and present, that purport to facilitate nasal breathing after nasal/sinus surgery, despite the nose being packed.

Some products, designed for dual packing-airway function, insinuate a pliable airway within a single piece of solid, foam-like packing material that expands when moistened.

Fabricated onto each of the pair of splints are one-half diameter, or “hemi-tubes,” designed to allow airflow. The Doyle septal splints are parabolic-shaped, and the attached hemi-tubes are curved to mirror normal airflow through the nose. The splint is seven cm long; the air tube is six cm; the hemi-tube has a radius of 4mm. Sold as a right-and-left pair, both members are inserted astride the septum and sutured to each other using a mattress suture across the septum. The aim is to stabilize the post-resection septal cartilage, return the previously elevated septal perichondrium against the cartilage, and promote readherence of mucosa to cartilage. To accomplish all this, the device must be secured to the cartilaginous septum through the mucosa, deep within the nasal passages, beyond the nostril opening, beyond the internal nasal valve, and even beyond the membranous septum. Thus, positioning of the splints relegates the anterior openings of the airway members to a position far inside the nasal fossae.

While this combination of a removable septal splint and an attached intranasal airway is conceptually attractive, the functional reality is that the nasal airway in-situ generally quickly becomes inoperative. Early in the post-operative period, the hemi-tubes promptly and irrevocably clog with blood and mucus. The deep-interior location effectively prohibits the patient or caretaker from gaining access to these anterior openings to keep the tubes from blocking. The air passage is now defunct.

The commonality to all deep-seated packing/airway hybrid devices are location-based, post-operative inaccessibility. Other dual-purpose, removable packing devices, as mentioned earlier, are the Pure Pak® , Slik-Pak®, and Venti-Pak®.These products, into whose PVA foam centers are seated a tube to ostensibly carry air, have been somewhat disappointing. Because immediately after surgery the nasal fossae quickly fill with secretions, the relatively narrow airflow tube can become blocked. Plus, their openings are not easily accessible for post-op, home-care maintenance.

We need to recognize that patients (who may be sedated by medications) and/or caregivers are understandably reluctant to explore the nasal interior and reopen blocked tubes and reestablish functionality. They are justifiably intimidated and fearful of causing pain or “ruining” the operation. Realistically, laypeople should not be charged with performing intranasal procedures to reopen an inoperative medical device.

An Independent, Single-purpose Device Is the Better Answer for Post-operative Airway Maintenance

We have studied, evaluated, and analyzed the deficiencies and functional compromises of the dual-mission hybrids: the splint and airway and the packing and airway versions. Perhaps it is better not to merge two disparate missions into a single device. For better performance and patient comfort and satisfaction, perhaps it is wiser to separate the splinting/ packing and airway roles.

Since there is now an ever-increasing variety of packing devices, it seems advantageous to allow the surgeon to choose from among them. For any of these modern packing products, a dedicated, independent, and reliable device to provide the post-operative airway is an ideal teammate.

As a product of the above-mentioned studies, we have developed and fabricated a post-operative nasal airway device: a one-piece, dual-nasal airway appliance that is inserted by the surgeon at the end of the operation, before or after packing and/or optional septal splint placement. This device will provide a corridor for adequate air passage through both nasal passages without compromising splint’s or packing’s important functions. It is compatible with any current packing product.

A Study of Airflow Through the New Device Versus Through Existing Hybrid Airways

The clinical value of any airway appliance rests on the volume of air that passes through the air tube en route to the lungs. Pouiseuille’s Law*, which quantitates laminar airflow through a definable and measurable passage governs the analysis of nasal airway devices

Poiseuille determined that the wider the tube radius, the lower the airflow resistance. More importantly, the change in radius is not proportional to the change in resistance but yields a four-fold increase in resistance for a given reduction in radius. Therefore, a small change in radius significantly affects either flow rate or pressure drop required to achieve the same flow.8 If the lumen of the airway becomes obstructed or narrowed, the effective radius of air flow will be significantly reduced, negatively affecting air flow to the patient

Accepting that small increases in an air tube’s diameter increases airflow exponentially, it is possible to scientifically assess, applying Poiseuille’s Law, what might be a major difference in airflow through the single-mission new device contrasted with a popular airway-splint hybrid, the Doyle Septal Splint, and an airway-pack hybrid, the Venti-Pak®.

The flow through each member of the Post-operative Nasal Airway is 188.1 cm3/pa-s (or 376.2 cm3/pa-s through both tubes) based on a length of 7.5 cm and a radius (internal diameter) of 0.5 cm. Airflow through the Doyle Septal Splint is 14.7 cm3/pa-s (or 29.6 cm3/pa-s through both nostrils), based on a length of 6.2cm and radius of 0.5cm. Reflecting the airways’ differential diameters and length, the airflow through the new independent airway device is 12.8 times greater than that through the Doyle Septal Splint.

The Venti-Pak®, a prototypical airway-packing hybrid, has an air tube inside diameter of 4 mm. Using Poiseuille’s Law, the calculated airflow through a Venti-Pak® is 82.5 cm3/pa-s. While delivering greater air flow than thru the Doyle Septal Splint, the Venti-Pak(R), also delivers less air to the nasopharynx than the newer device

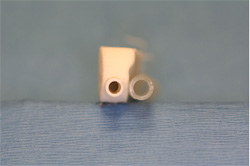

Comparative view of cross-sectional diameter of Venti-Pak with the post-operative nasal airyway

The Clinical Application of the Post-Operative Nasal Airway

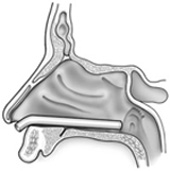

The tube is introduced at the conclusion of the operation prior to insertion of any packing, whether solid or gel. After initial, partial insertion, using a standard, thin-tip nasal speculum, inspect the nasal interior to ascertain the position of the airways within the nasal cavity.

The tube is introduced at the conclusion of the operation prior to insertion of any packing, whether solid or gel. After initial, partial insertion, using a standard, thin-tip nasal speculum, inspect the nasal interior to ascertain the position of the airways within the nasal cavity.

Under direct vision, advance the airways further into the nose. Next, using the inferior speculum blade or a bayonet forceps, direct each airway downward onto the floor.

Under direct vision, advance the airways further into the nose. Next, using the inferior speculum blade or a bayonet forceps, direct each airway downward onto the floor.

The tube will snap into place onto the floor of the nose and maintain that position,lateral to the pre-maxillary bone and medial to the inferior turbinate.

The tube will snap into place onto the floor of the nose and maintain that position,lateral to the pre-maxillary bone and medial to the inferior turbinate.

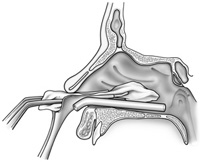

When both nasal tubes are properly seated, the bridge connecting the two will be flush against the columella. NOTE: If an open rhinoplasty procedure has been performed, the surgeon may wish to divide the bridge and secure each tube separately, rather than have the bridge contact the transcolumellar incision.

When both nasal tubes are properly seated, the bridge connecting the two will be flush against the columella. NOTE: If an open rhinoplasty procedure has been performed, the surgeon may wish to divide the bridge and secure each tube separately, rather than have the bridge contact the transcolumellar incision.

If the surgeon chooses to pack, packing material of choice is places as speculum stabilizes the nasal airway.

If the surgeon chooses to pack, packing material of choice is places as speculum stabilizes the nasal airway.

After insertion and seating of the nasal airway, the surgeon passes the 10Fr plastic suction catheter through each tube and suctions fluids from the pharynx. This maneuver also confirms that the back opening of the device is unobstructed. Later, the anesthesia specialist, using the same flexible suction catheter, will avail himself of this direct pathway to the pharynx for suctioning blood and mucous from throat.

After insertion and seating of the nasal airway, the surgeon passes the 10Fr plastic suction catheter through each tube and suctions fluids from the pharynx. This maneuver also confirms that the back opening of the device is unobstructed. Later, the anesthesia specialist, using the same flexible suction catheter, will avail himself of this direct pathway to the pharynx for suctioning blood and mucous from throat.

At the end of the procedure, prior to awakening the patient, the same 10 fr. plastic suction catheter is passed by the anesthesiologist through each nasal airway tube to suction the oropharynx. Our anesthesiologists expressed preference for such access into the pharynx for suctioning while the patient is still asleep, rather than having to struggle to perform oral-pharyngeal toilet, as the patient is emerging from anesthesia.

Home Care

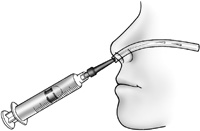

For home care, the patient is provided a 3cc Luer-Lok syringe and adapter tip. An illustrated instruction sheet, provided with the airway kit, explains the simple technique of irrigation with tap water, as needed, to maintain clear airways.

To prepare the patient for ease of tube and non-absorbable pack removal, five drops of an anesthetic-decongestant solution (equal volumes of oxymetrazolamine and tetracaine 2%), were instilled into the nasal cavities to anesthetize and decongest the mucosa in anticipation of tube and pack removal. The tubes easily slid out of the nasal fossa, and the non-absorbable pads were likewise easily extracted. The absorbable packing was absent, and mucosal surfaces demonstrated early healing. There were no remnant signs of any internal damage from the indwelling tubes in any of the cases. Significantly, there was not a single episode of significant epistaxis at time of tube and pack removal that required intervention of any kind. One patient had a bleeding episode from a posterior turbinate resection site and from the posterior septoplasty site, 11days after surgery that required placement of absorbable packing.

The Clinical Experience: 114 Patient Case Histories

In the senior author’s practice, 114 patients scheduled to undergo reconstructive nasal surgery–nasal septoplasty and bilateral inferior turbinate resection, with or without rhinoplasty–were offered and consented to placement of the nasal airway.

Of this population, 19 patients had prior nasal surgery and had endured packing with complete nasal blockage. One patient within this subgroup had three failed prior septorhinoplasty procedures

In all cases, the senior author always inserted two different packings: one absorbable and one non-absorbable. The absorbable was a two-ply sheet of either gauzelike Surgicel® or absorbable hemostatic gauze ActCel® draped over the turbinate remnant. The removable pack was a folded (thus two-ply) single sheet of non-adherent Telfa® coated on both sides with tetracycline ointment. As a means to ease insertion of the absorbable packing (which becomes a bit unmanageable when moistened by mucus or blood), the ointment-coated, now surface-sticky Telfa® pad was used to “carry and deliver” the gauze to its home over the medial edge of the turbinate. Through this maneuver, the Telfa® pad was simultaneously placed favorably to fulfill its overall packing mission. A remnant suture from the surgical procedure is secured to the right and left Telfa® pads before insertion. This was tied to its opposite member over the columella or taped to the adjacent cheek, to anchor and prevent accidental posterior displacement of the Telfa® pad. The suture-string also facilitates the pack’s removal.

To prepare the patient for ease of tube and non-absorbable pack removal, five drops of an anesthetic-decongestant solution (equal volumes of oxymetrazolamine and tetracaine 2%), were instilled into the nasal cavities to anesthetize and decongest the mucosa in anticipation of tube and pack removal. The tubes easily slid out of the nasal fossa, and the non-absorbable pads were likewise easily extracted. The absorbable packing was absent, and mucosal surfaces demonstrated early healing. There were no remnant signs of any internal damage from the indwelling tubes in any of the cases. Significantly, there was not a single episode of significant epistaxis at time of tube and pack removal that required intervention of any kind. One patient had a bleeding episode from a posterior turbinate resection site and from a posterior septoplasty site, 11days after surgery that required placement of absorbable packing. The nasal airway had not been incontact with either bleeding location.

Of the 114 patients, 110 sustained the tube placement for either four or five days. Three patients requested removal because they were not interested in, or capable of, the home irrigation of the tubes necessary to maintain patency and airflow. One patient took it upon himself to remove the tubes after three days. No adverse consequences ensued from any premature removal.

Conclusion

Though nasal and sinus surgery is common and widespread, there is no consensus on choice of nasal packing. Further some surgeons prefer not to pack. Those who pack feel that nasal packing–in some form–is important to prevent post-operative complications such as synechiae, bleeding, and anatomic destabilization

Despite their importance and value, contemporary packing materials and devices and airway appliances generate patient dissatisfaction. Even those patients who do not endure packing are not satisfied with the airway immediately after surgery because of lining mucosal edema,and blood and mucus stasis. Pack or no-pack, nasal obstruction generates anxiety, claustrophobia, and negative public relations. For these routine and generally successful procedures to be rejected by patients because of post-operative dissatisfaction — which need not occur — is unfortunate. There are perhaps tens of thousands of potential patients who would be approaching nasal surgeons requesting the operation had the procedure’s bad public image not scared them off.

As a result of investigating the issue of patient comfort and safety in the nasal/sinus surgery post-operative period, the new medical device described in this report provides a safe airway that contributes to patient comfort and, ultimately, provides a more satisfactory post-surgical experience.

References

- Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. “Ambulatory Surgery in the United States, 2006.” National Center for Health Statistics. 2009. 11: 1-28.

- Warner J, Gutowski K, Shama L, et al. “National Interdisciplinary Rhinoplasty Survey.” Aesthetic Surgery Journal. 2009. 29(4): 295–301.

- Chheda N, Katz A, Gynizio L, Singer A. “The Pain of Nasal Tampon Removal After Nasal Surgery: A Randomized Control Trial.” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 2009. 140: 215-217.

- Weber R, Hochapfel F, Draf W. “Packing and Stents in Endonasal Surgery.” Rhinology. 2000. 38: 49-62.

- Ogretmenoglu O, Yilmaz T, Rahimi K, et al. “The Effect on Arterial Blood Gases and Heart Rate of Bilateral Nasal Packing.” Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002. 259: 63-6.

- Lubianca-Neto JF, Sant’anna GD, Mauri M, Arrarte JL, Brinckmann CA. “Evaluation of Time of Nasal Packing After Nasal Surgery: A Randomized Trial.” Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery. 2000. 122(6): 899-901.

- Arya AK, Butt O, Nigam A. “Double-blind Randomised Controlled Trial Comparing Merocel with Rapid Rhino Nasal Packs After Routine Nasal Surgery.” Rhinology. 2003. 41: 241-243.

- Fairbanks DNF. “Complications of Nasal Packing.” Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery. 1986. 94: 412-415.

- Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s Interactive Respiratory Physiology.

The authors acknowledge the input, advice, and suggestions — throughout the study and development of the new airway device — of the following colleagues and advisors: William Binder, MD; Joe Parell, MD; Ronald Strahan, MD; Robert Meyers, MD; Gary Becker, MD; Kenneth Geller, MD; Kevin Tehrani, MD; Sheldon Schneider, BS; Craig Sherman, JD; A. Norman Enright, BA, MBA; Lindsey Kotler, BA; Jerry Berliant; Doris Porter, RN, CNOR; DeLoris Everts, RN, CNOR; Toya Twitty, ORT; Tammi Jollata, CST.

Special thanks to Mary Jakubowitz , Talia Dadon and Aimy Cohen for their administrative assistance.

John Reid, Reid Medical, San Diego, CA, provided nasal endoscopic exam and recording equipment.

Airway device concept and prototype design by Burt Bochner, Culver City, CA and Art Schulenberger, San Leandro, CA.

Airway device fabrication by Robert Hallock, Concept Modelz, Livermore, CA.

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.